Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Difference between revisions

Johnrdorazio (talk | contribs) |

Johnrdorazio (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

A letter to Mrs von Meck on 16/28 February–17 February/1 March 1879, in which he tells her of his impressions of reading the scene in The Brothers Karamazov where Father Zosima has to comfort a woman who has lost all her children, shows that this was a question which Tchaikovsky often thought about: | A letter to Mrs von Meck on 16/28 February–17 February/1 March 1879, in which he tells her of his impressions of reading the scene in The Brothers Karamazov where Father Zosima has to comfort a woman who has lost all her children, shows that this was a question which Tchaikovsky often thought about: | ||

{{Quote|text=Yes, my friend! It is better to have to die oneself every day for a thousand years than to lose those whom one loves and to seek consolation in the hypothetical idea that we shall meet again in the other world! Will we meet again? Happy are those who manage not to have doubts about this|author=Pyotr Tchaikovsky|source=http://www.tchaikovsky-research.net/en/people/index.html}} | |||

On the subject of Tchaikovsky’s views on religion, it is very instructive to turn to his | On the subject of Tchaikovsky’s views on religion, it is very instructive to turn to his ''special diary''. On 22 February/6 March 1886, he noted there: | ||

{{Quote|text=What an infinitely deep abyss between the Old and the New Testament! Am reading the Psalms of David and do not understand why, first, they are placed so high artistically and, second, in what way they could have anything in common with the Gospel. David is entirely worldly. The whole human race he divides into two unequal parts: in one, the godless (here belongs the vast majority), in the other, the godly and at their head he places himself. Upon the godless, he invokes in each psalm divine punishment, upon the godly, reward; but both punishment and reward are earthly. The sinners will be annihilated; the godly will reap the benefits of all the blessings of earthly life. How unlike Christ who prayed for his enemies and to his fellow man promised not earthly blessings but the Kingdom of Heaven. What eternal poetry and, touching to tears, what feeling of love and pity toward mankind in the words: “Come unto me all ye that labor and are heavy laden.” All the Psalms of David are nothing in comparison with these simple words.|author=Pyotr Tchaikovsky|source=Wladimir Lakond, ''The Diaries of Tchaikovsky (1945), p. 244''}} | |||

This contrast between the Old and New Testament and his admiration for the figure of Christ, and, in particular, for Christ’s exhortation: “Come unto me all ye that labour and are heavy laden” ( | This contrast between the Old and New Testament and his admiration for the figure of Christ, and, in particular, for Christ’s exhortation: “Come unto me all ye that labour and are heavy laden” ({{Bible quote|version=NABRE|ref=Matthew 11:28}}) — the underlying idea of which he once tried to set into music — are themes he often returned to in those years. Another interesting diary entry is that which he made in Maydanovo on 21 September/3 October 1887, on the same day that his old friend Nikolay Kondratyev died after a long illness in Aachen (where Tchaikovsky had visited him that summer): | ||

{{Quote|text=How strange it was for me to read that 365 days ago I was still afraid to acknowledge that, despite all the fervor of sympathetic feelings awakened by Christ, I dared to doubt His Divinity. Since then, my religion has become infinitely more clear; I thought much about God, about life and death during all that time, and especially in Aachen the vital questions: why? how? wherefore? occupied and hung over me disturbingly. I would like sometime to expound in detail my religion if only for the sake of explaining my beliefs to myself, once and for all, and the borderline where, after speculation, they begin. But life with its excitement rushes on, and I do not know whether I will succeed in expressing that Creed which recently has developed in me. It has developed very clearly, but still I have not adopted it as yet in my prayers. I still pray as before, as they taught me to pray. But then, God hardly needs to know how and why one prays. God does not need prayer. But we need it.|author=Pyotr Tchaikovsky|source=Wladimir Lakond, ''The Diaries of Tchaikovsky'' (1945), p. 249}} | |||

It is possible that the Fifth Symphony grew out of some of these reflections, as suggested by Tchaikovsky’s notes on the initial sketches (see the work history). | It is possible that the Fifth Symphony grew out of some of these reflections, as suggested by Tchaikovsky’s notes on the initial sketches (see the work history). | ||

Revision as of 03:13, September 9, 2020

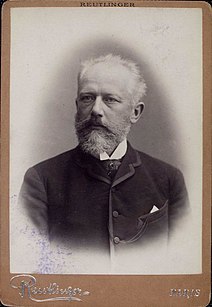

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky[a 2] (English: /tʃaɪˈkɒfski/ chy-KOF-skee;[1] Russian: Пётр Ильи́ч Чайко́вский,[a 3] IPA: [pʲɵtr ɪlʲˈjitɕ tɕɪjˈkofskʲɪj] (![]() listen); 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893[a 4]) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally. He was honored in 1884 by Tsar Alexander III and awarded a lifetime pension.

listen); 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893[a 4]) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally. He was honored in 1884 by Tsar Alexander III and awarded a lifetime pension.

Although musically precocious, Tchaikovsky was educated for a career as a civil servant. There was scant opportunity for a musical career in Russia at the time and no system of public music education. When an opportunity for such an education arose, he entered the nascent Saint Petersburg Conservatory, from which he graduated in 1865. The formal Western-oriented teaching that he received there set him apart from composers of the contemporary nationalist movement embodied by the Russian composers of The Five with whom his professional relationship was mixed.

Tchaikovsky's training set him on a path to reconcile what he had learned with the native musical practices to which he had been exposed from childhood. From that reconciliation, he forged a personal but unmistakably Russian style. The principles that governed melody, harmony and other fundamentals of Russian music ran completely counter to those that governed Western European music, which seemed to defeat the potential for using Russian music in large-scale Western composition or for forming a composite style, and it caused personal antipathies that dented Tchaikovsky's self-confidence. Russian culture exhibited a split personality, with its native and adopted elements having drifted apart increasingly since the time of Peter the Great. That resulted in uncertainty among the intelligentsia about the country's national identity, an ambiguity mirrored in Tchaikovsky's career.

Religious views

Tchaikovsky expresses his religious perspective in a letter to Nadezhda von Meck on 23 November/5 December 1877:

However, conviction is one thing, and instinct and feeling another. Whilst I deny an eternal afterlife, it is with indignation that I reject at the same time the monstrous thought that I shall never see again some loved ones who are now dead. In spite of the triumphant force of my convictions, I shall never reconcile myself to the thought that my mother, whom I so loved and who was such a wonderful person, has disappeared forever and that I will never be able to tell her that even after twenty-three years of separation I still love her the same

A letter to Mrs von Meck on 16/28 February–17 February/1 March 1879, in which he tells her of his impressions of reading the scene in The Brothers Karamazov where Father Zosima has to comfort a woman who has lost all her children, shows that this was a question which Tchaikovsky often thought about:

Yes, my friend! It is better to have to die oneself every day for a thousand years than to lose those whom one loves and to seek consolation in the hypothetical idea that we shall meet again in the other world! Will we meet again? Happy are those who manage not to have doubts about this

On the subject of Tchaikovsky’s views on religion, it is very instructive to turn to his special diary. On 22 February/6 March 1886, he noted there:

What an infinitely deep abyss between the Old and the New Testament! Am reading the Psalms of David and do not understand why, first, they are placed so high artistically and, second, in what way they could have anything in common with the Gospel. David is entirely worldly. The whole human race he divides into two unequal parts: in one, the godless (here belongs the vast majority), in the other, the godly and at their head he places himself. Upon the godless, he invokes in each psalm divine punishment, upon the godly, reward; but both punishment and reward are earthly. The sinners will be annihilated; the godly will reap the benefits of all the blessings of earthly life. How unlike Christ who prayed for his enemies and to his fellow man promised not earthly blessings but the Kingdom of Heaven. What eternal poetry and, touching to tears, what feeling of love and pity toward mankind in the words: “Come unto me all ye that labor and are heavy laden.” All the Psalms of David are nothing in comparison with these simple words.

— , Wladimir Lakond, The Diaries of Tchaikovsky (1945), p. 244

This contrast between the Old and New Testament and his admiration for the figure of Christ, and, in particular, for Christ’s exhortation: “Come unto me all ye that labour and are heavy laden” (Matthew 11:28) — the underlying idea of which he once tried to set into music — are themes he often returned to in those years. Another interesting diary entry is that which he made in Maydanovo on 21 September/3 October 1887, on the same day that his old friend Nikolay Kondratyev died after a long illness in Aachen (where Tchaikovsky had visited him that summer):

How strange it was for me to read that 365 days ago I was still afraid to acknowledge that, despite all the fervor of sympathetic feelings awakened by Christ, I dared to doubt His Divinity. Since then, my religion has become infinitely more clear; I thought much about God, about life and death during all that time, and especially in Aachen the vital questions: why? how? wherefore? occupied and hung over me disturbingly. I would like sometime to expound in detail my religion if only for the sake of explaining my beliefs to myself, once and for all, and the borderline where, after speculation, they begin. But life with its excitement rushes on, and I do not know whether I will succeed in expressing that Creed which recently has developed in me. It has developed very clearly, but still I have not adopted it as yet in my prayers. I still pray as before, as they taught me to pray. But then, God hardly needs to know how and why one prays. God does not need prayer. But we need it.

— , Wladimir Lakond, The Diaries of Tchaikovsky (1945), p. 249

It is possible that the Fifth Symphony grew out of some of these reflections, as suggested by Tchaikovsky’s notes on the initial sketches (see the work history).

An interesting article by Elena Dyachkova, “Tchaikovsky and the Bible”, is available online:

http://www.uni-leipzig.de/~musik/web/institut/agOst/docs/mittelost/hefte/0515-Dychakova.pdf

... in which she also touches upon Tchaikovsky’s admiration for St Joan of Arc (the subject of another recent posting).

Music

Musical compositions by Tchaikovsky which were religiously inspired are:

The All-Night Vigil (Vesper Service), for unaccompanied chorus Op. 52 (1881-82)

- Introductory Psalm: Bless My Soul, O Lord

- Kathisma: Blessed is the Man

- Lord, I Call to Thee

- Gladsome Light

- Rejoice, O Virgin

- The Lord is God

- Polyeleion: Praise the Name of the Lord

- Troparia: Blessed Art Thou, Lord

- Gradual Antiphon: From My Youth

- Hymns after the Gospel Reading: Having Beheld the Resurrection of Christ

- Common Katabasis: I Shall Open My Lips

- Canticle of the Mother of God : Holy is the Lord Our God

- Theotokion: Both Now and Forever

- Great Doxology: Glory to God in the Highest

- To Thee the Glorious Leader

The Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom

See Liturgy_of_St._John_Chrysostom_(Tchaikovsky).

Tchaikovsky, known primarily for his symphonies, concertos and ballets, was deeply interested in the music and liturgy of the Russian Orthodox Church. In 1875, he compiled A Concise Textbook of Harmony Intended to Facilitate the Reading of Sacred Musical Works in Russia.[2]

The Cherubikon is the usual Cherubic Hymn sung at the Great Entrance of the Byzantine liturgy. The hymn symbolically incorporates those present at the liturgy into the presence of the angels gathered around God's throne.

Legend

See Legend (Tchaikovsky).

Legend (Russian: Легенда, Legenda), Op. 54, No. 5 (also known as The Crown of Roses in some English-language sources)[1] is a composition by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Originally written in 1883 as a song for solo voice and piano, it was subsequently arranged by Tchaikovsky for solo voice and orchestra (1884), and then for unaccompanied choir (1889).[2] The words are based on the poem "Roses and Thorns" by American poet Richard Henry Stoddard, originally published in Graham's Magazine of May 1856.[2][3] :

The young child Jesus had a garden

Full of roses, rare and red;

And thrice a day he watered them,

To make a garland for his head!

When they were full-blown in the garden,

He led the Jewish children there,

And each did pluck himself a rose,

Until they stripped the garden bare!

"And now how will you make your garland?

For not a rose your path adorns:"

"But you forget," he answered them,

"That you have left me still the thorns.

They took the thorns, and made a garland,

And placed it on his shining head;

And where the roses should have shone,

Were little drops of blood instead!— , Stoddard, R[ichard] H[enry] (May 1856). "Roses and Thorns". Graham's Magazine. Philadelphia. xlviii (5): 414.

Notes

- ↑ Published in 1903

- ↑ Often anglicized as Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky; also standardized by the Library of Congress. His names are also transliterated as Piotr or Petr; Ilitsch or Il'ich; and Tschaikowski, Tschaikowsky, Chajkovskij, or Chaikovsky. He used to sign his name/was known as P. Tschaïkowsky/Pierre Tschaïkowsky in French (as in his afore-reproduced signature), and Peter Tschaikowsky in German, spellings also displayed on several of his scores' title pages in their first printed editions alongside or in place of his native name.

- ↑ Петръ Ильичъ Чайковскій in Russian pre-revolutionary script.

- ↑ Russia was still using old style dates in the 19th century, rendering his lifespan as 25 April 1840 – 25 October 1893. Some sources in the article report dates as old style rather than new style.

References

- ↑ "Tchaikovsky". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ "Peter Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)". Musica Russica. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

Sources

- Asafyev, Boris (1947). "The Great Russian Composer". Russian Symphony: Thoughts About Tchaikovsky. New York: Philosophical Library.

- Benward, Bruce; Saker, Marilyn (200). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. 1 (Seventh ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- Botstein, Leon (1998). "Music as the Language of Psychological Realm". In Kearney, Leslie (ed.). Tchaikovsky and His World. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00429-3.

- Brown, David, "Glinka, Mikhail Ivanovich" and "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich". In The New Grove Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillan, 1980), 20 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Early Years, 1840–1874 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978). ISBN 0-393-07535-4.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Crisis Years, 1874–1878, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983). ISBN 0-393-01707-9.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Years of Wandering, 1878–1885, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1986). ISBN 0-393-02311-7.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 1885–1893, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991). ISBN 0-393-03099-7.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music (New York: Pegasus Books, 2007). ISBN 0-571-23194-2.

- Cooper, Martin, "The Symphonies". In Music of Tchaikovsky (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1946), ed. Abraham, Gerald. ISBN n/a. OCLC 385829

- Druckenbrod, Andrew, "Festival to explore Tchaikovsky's changing reputation". In Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 30 January 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Figes, Orlando, Natasha's Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002). ISBN 0-8050-5783-8 (hc.).

- Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995). ISBN 0-679-42006-1.

- Holoman, D. Kern, "Instrumentation and orchestration, 4: 19th century". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Hopkins, G. W., "Orchestration, 4: 19th century". In The New Grove Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillan, 1980), 20 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Hosking, Geoffrey, Russia and the Russians: A History (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001). ISBN 0-674-00473-6.

- Jackson, Timothy L., Tchaikovsky, Symphony no. 6 (Pathétique) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999). ISBN 0-521-64676-6.

- Karlinsky, Simon, "Russia's Gay Literature and Culture: The Impact of the October Revolution". In Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past (New York: American Library, 1989), ed. Duberman, Martin, Martha Vicinus and George Chauncey. ISBN 0-452-01067-5.

- Kozinn, Allan, "Critic's Notebook; Defending Tchaikovsky, With Gravity and With Froth". In The New York Times, 18 July 1992. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Lockspeiser, Edward, "Tchaikovsky the Man". In Music of Tchaikovsky (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1946), ed. Abraham, Gerald. ISBN n/a. OCLC 385829

- Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). ISBN 0-520-21815-9.

- Mochulsky, Konstantin, tr. Minihan, Michael A., Dostoyevsky: His Life and Work (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967). LCCN 65-10833.

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man (New York: Schirmer Books, 1991). ISBN 0-02-871885-2.

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky Through Others' Eyes. (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1999). ISBN 0-253-33545-0.

- Ridenour, Robert C., Nationalism, Modernism and Personal Rivalry in Nineteenth-Century Russian Music (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1981). ISBN 0-8357-1162-5.

- Ritzarev, Marina, Tchaikovsky's Pathétique and Russian Culture (Ashgate, 2014). ISBN 9781472424112.

- Roberts, David, "Modulation (i)". In The New Grove Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillan, 1980), 20 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Rubinstein, Anton, tr. Aline Delano, Autobiography of Anton Rubinstein: 1829–1889 (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1890). Library of Congress Control Number LCCN 06-4844.

- Schonberg, Harold C. Lives of the Great Composers (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 3rd ed. 1997). ISBN 0-393-03857-2.

- Steinberg, Michael, The Concerto (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

- Steinberg, Michael, The Symphony (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- Taruskin, Richard, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il'yich", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera (London and New York: Macmillan, 1992), 4 vols, ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 0-333-48552-1.

- Volkov, Solomon, Romanov Riches: Russian Writers and Artists Under the Tsars (New York: Alfred A. Knopf House, 2011), tr. Bouis, Antonina W. ISBN 0-307-27063-7.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky Symphonies and Concertos (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969). LCCN 78-105437.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973). ISBN 0-684-13558-2.

- Wiley, Roland John, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Wiley, Roland John, The Master Musicians: Tchaikovsky (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009). ISBN 978-0-19-536892-5.

- Zhitomirsky, Daniel, "Symphonies". In Russian Symphony: Thoughts About Tchaikovsky (New York: Philosophical Library, 1947). ISBN n/a.

- Zajaczkowski, Henry, Tchaikovsky's Musical Style (Ann Arbor and London: UMI Research Press, 1987). ISBN 0-8357-1806-9.

Further reading

- Bergamini, John, The Tragic Dynasty: A History of the Romanovs (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1969). LCCN 68-15498.

- Bullock, Philip Ross (2016). Pyotr Tchaikovsky. London, U.K.: Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780236544. OCLC 932385370.

- Hanson, Lawrence and Hanson, Elisabeth, Tchaikovsky: The Man Behind the Music (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company). LCCN 66-13606.

External links

- Tchaikovsky Research

- "Discovering Tchaikovsky". BBC Radio 3.

- Tchaikovsky cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at the Internet Broadway Database

- Works by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at Internet Archive

- Piotr Ilitch Tchaïkovski – Musique Classique – medici.tv

- Mutopia Project Tchaikovsky Sheet Music at Mutopia

- Free scores by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Tchaikovsky Arias and Piano works performed live in Brussels

- Articles with short description

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Use dmy dates from May 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles containing Russian-language text

- Articles with hAudio microformats

- Bible quote template

- CS1: long volume value

- Commons category link is the pagename

- Articles with IBDb links

- Articles with Project Gutenberg links

- Articles with Internet Archive links

- Composers with IMSLP links

- Articles with International Music Score Library Project links

- Portal templates with all redlinked portals

- AC with 0 elements

- Pages with red-linked authority control categories

- Featured articles

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

- 19th-century classical composers

- Classical composers of church music

- Composers for piano

- Russian ballet composers

- Russian classical composers

- Russian classical pianists

- Russian opera composers